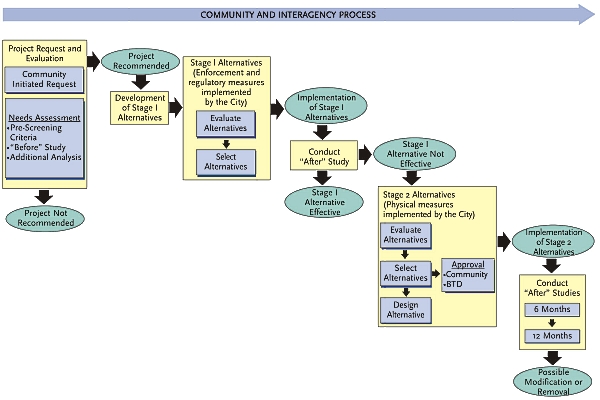

To begin, following a "Community Initiated Request" there must be a "pre-screening" and a "before" study:

The prescreening criteria include basic roadway characteristics that allow the BTD to determine if implementing transportation safety improvement measures are appropriate for residential streets. [...] First, the study will establish a traffic baseline from which the effectiveness of the project can be compared to later. The second purpose is to collect data to perform a level of screening to ensure that it is still appropriate to consider transportation safety improvement measures.

Then BTD will consider some simple regulatory or sign changes, known as "Stage 1 alternatives." If that fails in the "after" study, then they will only consider physical changes for pedestrian safety if: (a) the road is under 40 feet wide, (b) not an emergency or bus route, (c) no more than one lane in each direction, (d) not too steep, and (e) not curved too much. There's more. For Stage 2 changes, a neighborhood organization must be formed to study the options. Ultimately, it suggests that a petition with 75% neighborhood support must be submitted, and it must also receive 100% of support from immediate abutters. And the City retains the right to refuse the proposal. And you must find funding through a source such as TEA-21, AAA, or squeezing it out of adjacent development projects. The Stage 2 modifications cannot cause adverse effects to neighboring roads, either.

Considering all that, I'm surprised that any of these pedestrian safety proposals were ever implemented.

The above document claims to be a companion to the BTD streetscape guidelines for major roads.

The purpose of these guidelines is to provide for the equitable sharing of the public right-of-way between motor vehicles, pedestrians, bicycles, and transit.Let's take a look at some of the design elements of Boston streets:

Travel lanes for straight sections of a roadway should be a minimum of 11.5 feet (3.5 meters). According to Massachusetts Highway Department definitions, the minimum width for Urban Arterials is 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) and 11 feet (3.4 meters) for Urban Collectors, with or without a median.But we're talking about city streets with mixed uses. Why would we apply highway arterial standards to a place where people are expected to walk? And the appendix really says that Urban Collector lane minimum width is 3.25m, while Urban Local lane minimum width is 2.75m. That's actually a bit more reasonable. It makes a big difference to pedestrians when a four lane road requires 3-4 fewer meters of width for traffic. For example, the River St bridge project is taking advantage of lane narrowing (down from nearly 4m) to provide wider sidewalks and bicycle lanes.

The location of bus stops on bulb outs should be considered where the curb-lane is a parking lane.Excellent idea. I wonder why this recommendation has been largely ignored by the city.

For safety reasons mid-block crossings should not be provided where they would interfere with the queue area of an adjacent intersectionThis is incredibly vague. "Queue area" could extend arbitrarily far back. How can this be a safety issue? Unfortunately, I suspect this kind of excuse may have been used to remove a crosswalk in my neighborhood, recently.

Crosswalks should not be constructed with a different material than the rest of the street unless it is durable and will not have joints or cracks that interfere with the safety of pedestrians and bicyclists. For example, uneven materials like cobblestones should be avoided.Doesn't that conflict with the other guidelines? "In the South End, street direction changes were accompanied by intersections and roadway improvements that included curb extensions at intersections and textured pavement at crosswalks, and other right-of-way changes." I suppose that textured pavement could mean something else, but it sounds a lot like "uneven materials" to me.

Finally, we get to some good goals:

- Design intersections to provide a safe and efficient flow of vehicles, pedestrians and bicycles.

- Minimize pedestrian wait times at intersections.

Sounds nice. But I don't think they ever took these guidelines to heart. Looking at the reconstruction of Kenmore Square, the island hopping necessitated has become something of a joke. It will take several cycles of the lights to legally cross, on foot, the Square. And at each point, you have to go and press a button of the weird new electronic variety. And then stand there and wonder why you don't have a Walk signal, when the cars have a red light, and there aren't any possible conflicts. No wonder nobody bothers to wait.

- At intersections with heavy pedestrian use, maximize pedestrian Walk in the signal phasing cycle.

The PDF also happens to feature a picture of the main Allston Village intersection of Brighton and Harvard. This intersection has pedestrian traffic almost 24 hours a day. Yet, the city stubbornly refuses to consider removing the need for pedestrian beg-button activation in order to obtain the exclusive Walk phase, and also refuses to consider concurrent Walk. Although this is a free-walking town, for the most part, people do try to wait for the frenetic traffic here to subside. However, the beg-buttons often malfunction, leading to the absurd scene of dozens of pedestrians overflowing into the street because the cycle skipped over them, yet again.

I'm familiar with a number of the examples that were given in the documents, from the South End, Allston, Back Bay, and Downtown areas. I have to wonder, though, if all those changes were done around the same time, and then these documents were left to rot on the website for the past ten years.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.